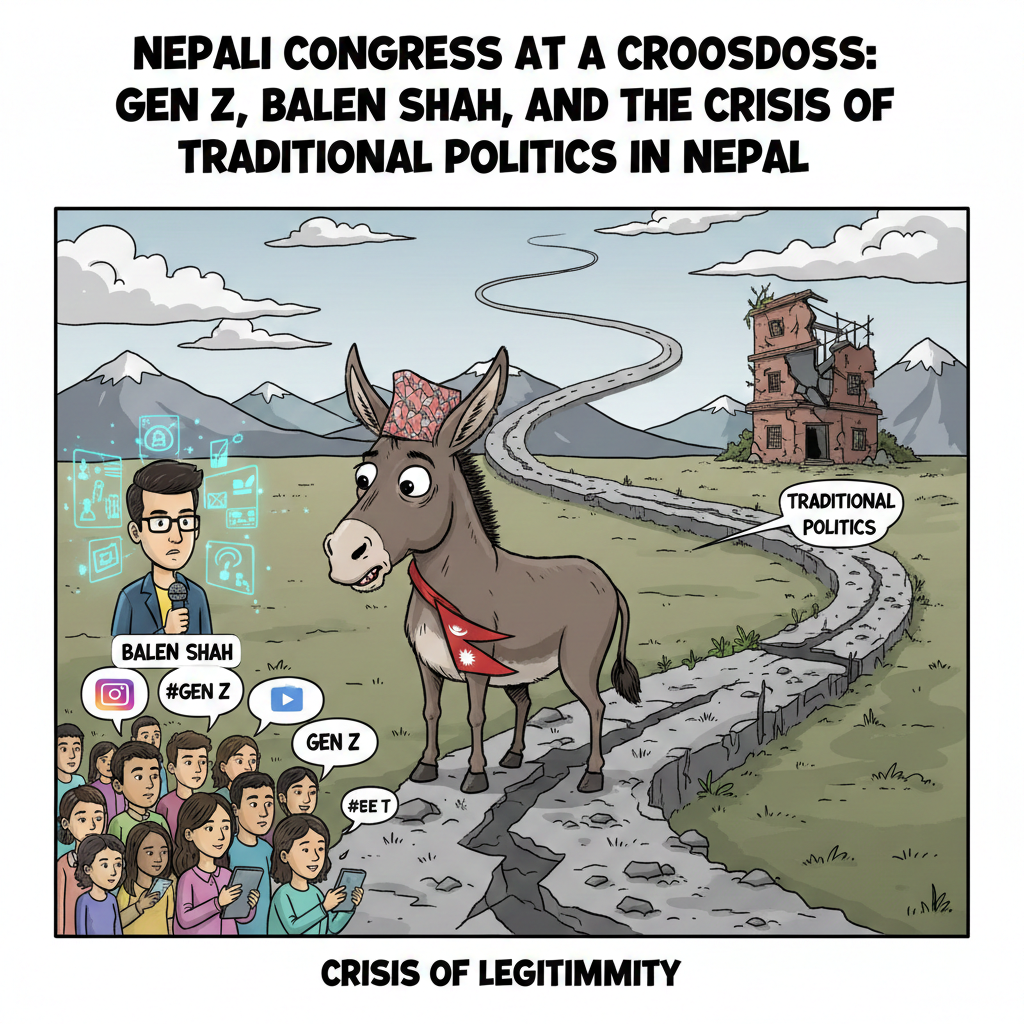

KATHMANDU – There's a battle brewing in Nepal's streets, and it's not the kind anyone expected. On one side: millions of young Nepalis who've had enough of the old way of doing things. On the other: KP Sharma Oli, a 73-year-old political heavyweight who seems determined to push back against a tide he can't really stop.

It's the classic story—old guard meets new energy—but with higher stakes than usual. Nearly half of Nepal's population is under 40, and they're not asking politely for a seat at the table anymore. They're demanding it. And Oli? He's building walls instead of bridges.

When "Volunteers" Sound More Like a Threat

Last November, Oli did something that raised eyebrows across Kathmandu. He created the National Volunteer Force, or NVF—supposedly to maintain order. But here's the thing: the timing was suspicious, coming just months after massive youth protests forced him out of power.

At the launch, Oli didn't mince words. "If anyone tries to lead the country down an undemocratic path, tries to create anarchy, and resorts to arson, vandalism, and terror, the volunteers will stop them," he declared. He called the September protesters "pseudo Gen Z groups" creating "disorder in the name of youth."

Pseudo. Let that word sink in. These weren't fringe troublemakers—these were thousands of ordinary young Nepalis fed up with corruption and broken promises. But to Oli, they were fake youth, troublemakers, problems to be solved.

Then came the really concerning part: he appointed Pushpa Raj Shrestha to lead this volunteer force. Shrestha isn't exactly a reassuring choice—he's facing four attempted murder charges and a kidnapping case. At his first speech, he told volunteers they were "ready to fight and confront—on the streets or anywhere—wearing red bands on our heads."

Red bands. Street confrontations. It doesn't exactly scream "democratic engagement," does it?

The Rules Are Different When You're In Charge

Here's where Oli's approach gets particularly frustrating for young people. In September 2024, he stood at Columbia University in New York and told Nepali youth abroad to "return home and create employment opportunities." Nice words. Inspiring, even.

But back home, his party was quietly rewriting its own rules. That same September, at a party convention Oli dominated, they scrapped two critical provisions: the 70-year age limit for leaders and the two-term restriction on executive positions. These were meant to ensure fresh blood could rise through the ranks.

Why remove them? So Oli could run for—and win—his third term as party chairman in December, securing 1,663 delegate votes. The message was clear: age limits are great for keeping young people out, but inconvenient when they apply to me.

Meanwhile, Nepal's laws already make it tough for young people to participate. You have to be 25 to run for parliament, 35 for the National Assembly. In the dissolved House of Representatives, only 11 percent of members were under 40. Yet youth make up 52 percent of registered voters.

Do the math. More than half the electorate is being represented by just over one-tenth of parliament.

"We Support Youth!" (But Not Really)

On December 13, at his party's national congress, Oli pushed back against accusations that established parties oppose youth participation. He called such claims "misleading."

A week later, on December 20, youth activists had had enough of what they called his "crassness"—his stubborn refusal to take their movement seriously.

And they have a point. One of Oli's key lieutenants on youth issues, Mahesh Basnet, has been blunt about the party's stance: "Wherever there is obstruction in the name of Gen Z, there will be resistance." In late November, that rhetoric turned violent when UML party workers clashed with youth protesters in Dhangadhi—the second such incident within a week.

This is what frustrates young activists like lawyer Anjalika Sinha, who puts it simply: "Corruption isn't only about money—it's also about the hunger for power. Old leaders dominate these positions, blocking fresh ideas from taking root."

The Numbers Don't Lie

Research from the Democracy Resource Centre tells a damning story. People aged 51-60 hold 34.5 percent of parliamentary seats despite being just 8 percent of the population. The 61-70 age group? They control 29.1 percent of seats. Most committee chairs and ministers are between 60 and 80 years old.

Researcher Nirashi Thami, who studies youth political exclusion, explains the systemic problem: "The laws and constitutional rules often block young people from participating fully in politics, and even when there are provisions to ensure their participation, they are not properly enforced. Parties talk about including youth, but in practice, they rarely give them real opportunities in leadership or candidate selection."

Oli's own party has a youth wing called Yuva Sangh. But real power? That flows through a tight circle where Oli, 80-year-old former PM Sher Bahadur Deuba, and 70-year-old Maoist leader Pushpa Kamal Dahal have been rotating control for decades.

Even His Own Party Has Doubts

Here's something interesting: not everyone in Oli's party thinks the NVF was a good idea. At a November 21 meeting, senior leaders including vice-chairman Ishwar Pokhrel openly opposed it.

"We already have a youth wing in the party. We do not need a parallel youth unit at this moment," Pokhrel argued. Another leader, Surendra Pandey, went further, calling the NVF a "militant-like youth organisation" unsuitable for a democratic party.

Party insiders worry that Oli's hardline approach could backfire in the March 2026 elections. Some privately admit that "rejecting the September protests will alienate the youth" and suspect Oli is "using the party's institutional strength to shield himself from potential action over his role in those events."

What Young People Actually Want

The Gen Z movement isn't asking for the moon. Their demands are straightforward: direct election of the prime minister, term limits for leaders, a citizen-led committee to investigate corruption, and voting rights for Nepali citizens living abroad.

These aren't radical ideas. In many democracies, they'd be standard practice. But in Nepal, where the same faces have dominated politics for decades, they represent a fundamental challenge to how power works.

Oli has occasionally acknowledged youth concerns, saying "we see a lot of potentials for [Nepal's] prosperity." But his actions consistently tell a different story—treating youth movements as security threats rather than legitimate voices demanding change.

The Turning Point

Last September changed everything. Between September 4 and 9, Gen Z protests exploded across Nepal. Twenty-two people were killed. The pressure became unbearable, and Oli resigned.

But resignation didn't mean acceptance. Within weeks, he was maneuvering—removing age limits, consolidating control, setting up the volunteer force. By December, he was back as party chairman, seemingly convinced he could weather the storm.

Now, as Nepal heads toward March 2026 elections with 18.9 million eligible voters, the question isn't whether young people will participate. They've already shown they will—loudly and persistently. The question is whether Nepal's old guard, personified by Oli, will finally listen.

Other parties—the Nepali Congress, the Nepali Communist Party led by Dahal—have committed to contesting the elections. But Oli continues demanding reinstatement of the dissolved parliament, seemingly out of step with both democratic norms and public sentiment.

What Happens Next?

Nepal stands at a crossroads. Nearly half its population is under 40, politically awakened, and tired of being shut out. They're not going away. They're not staying quiet.

Oli can keep building volunteer forces and dismissing protesters as "pseudo youth." He can keep his grip on party machinery and defend the status quo. But demographics don't lie, and neither does history. Every generation eventually gets its turn.

The only question is whether the transition happens through adaptation or confrontation, through listening or resistance, through evolution or crisis.

Right now, watching KP Sharma Oli, it seems he's chosen his path. And Nepal's young people? They've chosen theirs too.